ADAM SIMPSON & NICHOLAS FARRELLY

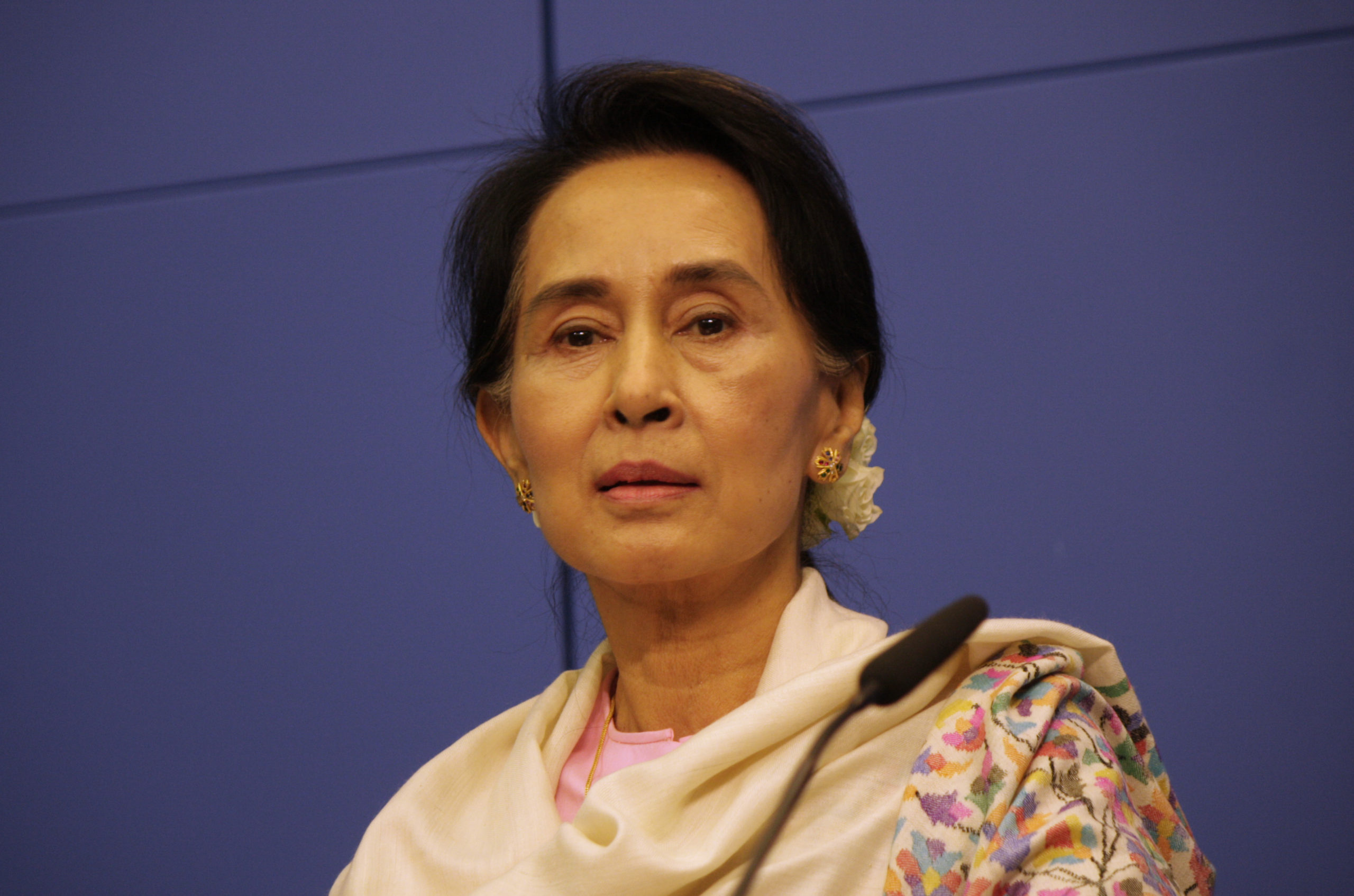

Just before the newly elected members of Myanmar’s parliament were due to be sworn in today, the military detained the country’s de facto leader, Aung San Suu Kyi; the president, Win Myint; and other key figures from the elected ruling party, the National League for Democracy.

The military later announced it had taken control of the country for 12 months and declared a state of emergency. This is a coup d’etat, whether the military calls it that or not.

A disputed election and claims of fraud

In November, the NLD and Suu Kyi won a landslide victory in national elections, with the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) faring poorly in its key strongholds.

Humiliated by the result, the USDP alleged the election was subject to widespread fraud. However, international observers, including the Carter Center, the Asian Network for Free Elections and the European Union’s Election Observation Mission, all declared the elections a success. The EU’s preliminary statement noted that 95% of observers had rated the process “good” or “very good”.

Reputable local organisations, such as the People’s Alliance for Credible Elections (PACE), agreed. These groups issued a joint statement on January 21 saying

the results of the elections were credible and reflected the will of the majority voters.

Yet, taking a page out of former US President Donald Trump’s book, the USDP pressed its claims of fraud despite the absence of any substantial evidence — a move designed to undermine the legitimacy of the elections.

The military did not initially back the USDP’s claims, but it has gradually begun to provide the party with more support, with the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, General Min Aung Hlaing, refusing to rule out a coup last week.

The following day, the country’s election authorities broke weeks of silence and firmly rejected the USDP’s claims of widespread fraud — setting the stage for what Myanmar historian Thant Myint-U called

[Myanmar’s] most acute constitutional crisis since the abolition of the old junta in 2010.

The civilian-military power-sharing arrangement

It is difficult to see how the military will benefit from today’s actions, since the power-sharing arrangement it had struck with the NLD under the 2008 constitution had already allowed it to expand its influence and economic interests in the country.

The military had previously ruled Myanmar for half a century after General Ne Win launched a coup in 1962. A so-called internal “self-coup” in 1988 brought a new batch of military generals to power. That junta, led by Senior General Than Shwe, allowed elections in 1990 that were won in a landslide by Suu Kyi’s party. The military leaders, however, refused to acknowledge the results.

In 2008, a new constitution was drawn up by the junta which reserved 25% of the national parliament seats for the military and allowed it to appoint the ministers of defence, border affairs and home affairs, as well as a vice president. Elections in 2010 were boycotted by the NLD, but the party won a resounding victory in the next elections in 2015.

Since early 2016, Suu Kyi has been de facto leader of Myanmar, even though there is still no civilian oversight of the military. Until this past week, the relationship between civilian and military authorities was tense at times, but overall largely cordial. It was based on a mutual recognition of overlapping interests in key areas of national policy.

Indeed, this power-sharing arrangement has been extremely comfortable for the military, as it has had full autonomy over security matters and maintained lucrative economic interests.

The partnership allowed the military’s “clearance operations” in Rakhine State in 2017 that resulted in the exodus of 740,000 mostly Muslim Rohingya refugees to Bangladesh.

In the wake of that pogrom, Suu Kyi vigorously defended both the country and its military at the International Court of Justice. Myanmar’s global reputation — and Suu Kyi’s once-esteemed personal standing — suffered deeply and never recovered.

Nonetheless, there was one key point of contention between the NLD and military: the constitutional prohibitions that made it impossible for Suu Kyi to officially take the presidency. Some NLD figures have also voiced deep concerns about the permanent role claimed by the armed forces as an arbiter of all legal and constitutional matters in the country.

A backwards step for Myanmar

Regardless of how events unfold this week and beyond, Myanmar’s fragile democracy has been severely undermined by the military’s actions.

The NLD government has certainly had its shortcomings, but a military coup is a significant backwards step for Myanmar — and is bad news for democracy in the region.

It’s difficult to see this action as anything other than a way for General Min Aung Hlaing to retain his prominent position in national politics, given he is mandated to retire this year when he turns 65. With the poor electoral performance of the USDP, there are no other conceivable political routes to power, such as through the presidency.

A coup will be counterproductive for the military in many ways. Governments around the world will likely now apply or extend sanctions on members of the military. Indeed, the US has released a statement saying it would “take action” against those responsible. Foreign investment in the country — except perhaps from China — is also likely to plummet.

As Myanmar’s people have already enjoyed a decade of increased political freedoms, they are also likely to be uncooperative subjects as military rule is re-imposed.

The 2020 general election demonstrated, once again, the distaste in Myanmar for the political role of the armed forces and the enduring popularity of Suu Kyi. Her detention undermines the fragile coalition that was steering Myanmar through a perilous period, and could prove a messy end to the profitable détente between civilian and military forces.

This article was originally posted on The Conversation.

Adam Simpson is Program Director of the Master of Communication in Justice & Society at the University of South Australia.

Professor Nicholas Farrelly is a Partner at Lydekker. You can see his full bio here.